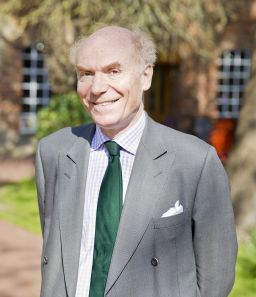

Editor’s Note: Dr. Terence Kealey is an adjunct scholar at the Cato Institute and a professor of clinical biochemistry at the University of Buckingham in the United Kingdom, where he served as vice chancellor until 2014. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion at CNN.

South Korea, the US and the UK all reported their first Covid-19 cases around the same time: on January 20, January 21, and January 31, respectively. How things unfolded from there, unfortunately for the US and UK, has been strikingly different.

Today, South Korea is reporting less than 100 new cases a day, the UK is reporting around 4,000 new cases a day, and the US is reporting around 30,000. But while numbers in South Korea have fallen, in the US and UK they have been rising exponentially (around 20,000 new cases a day a week ago, about 8,000 new cases a day a week before that). We don’t yet know if the exponential rise in the US has been halted or not, or whether the figure will plateau at around 30,000 new cases a day.

Nonetheless, the great success story is South Korea, and we know how they did it: they tested.

On December 31, 2019, Chinese officials informed the World Health Organization they had identified an unknown pneumonia, and on January 10, with impressive speed, Professor Yong-Zhen Zhang of Fudan University, Shanghai, published the virus’s RNA sequence. (An RNA sequence can be used as the basis of a diagnostic test.)

By February 4, Kogene Biotech of Seoul had not only developed one but had also had it approved by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC). And by February 10, was reporting its findings on the first 2,776 people to have been tested.

At that point, there were only 27 confirmed cases in South Korea, so – in another impressive demonstration of speed – the South Korean authorities tested each of them and, more importantly, isolated those who tested positive and monitored their contacts.

Initially, the authorities were swamped by the numbers of people who needed testing, but South Korean officials have tested contacts of those who have been infected. The authorities have made tests freely available and set up drive-in stations, modeled on McDonald’s and Starbucks for anyone to use. Those who tested positive were then isolated, with the result that the epidemic was swiftly controlled without the country as a whole needing to be shut down.

In the US and many other countries, however, a lack of testing kits prohibited the identification and isolation of individuals, so whole populations and whole economies have had to close down instead. By comparison, South Korea has been spared that fate partly by the government’s response and partly by the swift reaction of its biotech industry.

After Kogene’s test was approved, a second company, Seegene, got its own approved on February 12, and two more, SolGent and SD Biosensor, got theirs approved on February 27.

Yet the US and many of its peers could have been prepared.

President Barack Obama, for example, had established the Directorate for Global Health Security and Biodefense within the National Security Council, specifically to anticipate pandemics such as Covid-19. But two years ago, the Trump administration forced out the directorate’s leadership and fused its rump into a new directorate for counterproliferation.

Asked if the novel coronavirus had prompted him to reconsider his support for cuts to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the World Health Organization, President Trump replied, “I’m a business person – I don’t like having thousands of people around when you don’t need them. When we need them, we can get them back very quickly.”

Yet the people who can tell Trump when he needs them are the very people he doesn’t like having around. If you wait for doctors by the bedsides to tell you lots of people have fallen ill, it’s too late to prevent a disease from becoming a pandemic.

Trump’s lack of seriousness, compared with South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s, has been pointed.

On January 30, President Moon was saying that preventative “measures should be strong enough to the point of being considered excessive.” Trump, on the other hand, spent most of February saying the disease was no more of a threat than the flu, that it would suddenly disappear, and would later blame the “Fake News media” for criticism of his response.

Britain under Boris Johnson has been as insouciant. Johnson advocated striking a balance between restrictive measures and a strategy of “taking it on the chin,” under which increasing numbers of people would become infected until the virus would “move through the population.”

But, as the interviewers protested during the very interview at which Johnson revealed his strategy, his policy was bound to fail because Britain’s hospitals, under its single-payer National Health Service, lacked the capacity to handle the influx.

In pursuit of efficiency, Britain’s hospitals have little spare capacity, and it would take very few extra patients to swamp them. As, indeed, swiftly came to pass: Britain has instituted a virtual lockdown nationwide, while the US has issued federal guidelines on social distancing but continues to operate under a patchwork of state and local orders on what kinds of businesses can remain open and whether citizens can gather.

Neither has gone as far as China’s lockdown in Wuhan, which included a ban on travel in and out of the area, unless citizens were rated as safe to move about by a phone app that tracked likelihood of infectious contact.”

South Korea was sensitive to the dangers of the virus because of the country’s experience with SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, which spread in 2002 and 2003) and MERS (the Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus of the 2015 South Korean outbreak).

In establishing the Directorate for Global Health Security and Biodefense within the National Security Council, Obama evidently had hoped to preempt future pandemics, bringing US policy closer in line with more-prepared countries like South Korea. But perhaps he was flouting human nature. Perhaps we’re not very good, as a species, in learning from the experiences of others.

In the 1722 “Journal of the Plague Year,” describing the bubonic plague in London in 1665, Daniel Defoe wrote of “the Supine Negligence of the People themselves, who during the long Notice, or Warning, they had of the Visitation, yet made no Provision for it.” When Trump recently said that Covid-19 was something “you can never really think is going to happen,” he may have been speaking for anyone who resists preparing for abstract dangers.

The British populist politician Michael Gove in 2016 spoke for similar swaths in the UK when he declared that “people in this country have had enough of experts.” Yet the one politician who has come out this crisis well is President Moon Jae-in of South Korea, who listened very carefully to the experts. There may be a lesson there.